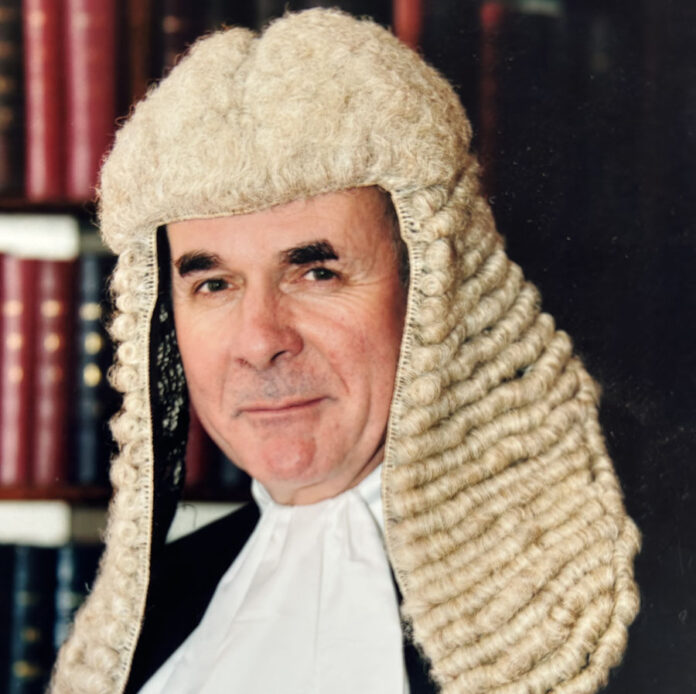

By Brian Lett KC, 4 King’s Bench Walk

I must confess to being a fervent supporter of the European Convention on Human Rights [which was drafted in large part by British lawyers], and of the Human Rights Act 1998. However, the cynic in me questions whether, in reality, human rights are not just the luxury of a settled and successful country, and are too often forgotten or brushed aside in times of national crisis such as war. The decision to go to war may be an involuntary one, as in the case of Ukraine today, but both the attacker and the defender will know that military violence of any kind will inevitably bring “collateral damage”, the deaths or injury of innocent civilians or the ruining of their homes and their lives. Too often mass violations of human rights are explained away by the excuse that the rockets or shells that caused them were being aimed at military targets, and it is claimed that they were therefore justifiable or proportionate. Any historian will know that in most of the conflicts of the past, the human rights of non-combatants have come a very poor second to the desire for victory, although afterwards, of course, there may be trials for war crimes where atrocities have occurred.

At the present time, the Government of the United Kingdom, which faces a General Election within the next twelve or fourteen months, claims to be fighting war against an invasion of illegal migrants on the south coast of England – some of them undoubtedly economic migrants, some of them potentially criminals, but many of them genuine refugees from abusive regimes, who believe that their future lies best in this country, known as it is for its justice and fairness to all. It is inappropriate for me in this article to dwell in any detail on the measures which the present government is trying to implement to prevent this invasion – deportation to Rwanda, incarceration in poor quality accommodation on “prison” ships, and, it is said, removing Disney cartoons from the walls of children’s detention homes in order to prevent them from having too happy a time in this country. This author found it difficult to believe the latter when he first heard it, but apparently it is true. Today, observers comment that the British Government finds some aspects of the provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, the Human Rights Act 1998 and the European Court of Human Rights an inconvenience. In the face of an increasing flow of “boat people” arriving on the South Coast, the Government has promised to take decisive action, and sadly the temptation may be to ignore the fact that each and every migrant, adult or child, has certain basic human rights which the law demands should be respected.

Therefore, a cautionary tale – may I remind us all about what happened the last time a United Kingdom Government tried to deport migrants en masse from this country. In 1940, Britian was at war with Nazi Germany. After the rise to power of Adolf Hitler in 1933, thousands of refugees, the vast majority Jewish, had sought shelter in the United Kingdom from Germany and Austria, and after careful vetting, were granted asylum here. The “kindertransport” carried numerous Jewish children to what was believed to be the safety of the United Kingdom. Within the United Kingdom in 1938 and 1939, there were numerous acts of kindness and generosity extended towards those refugees – reflecting a respect for their human rights. They were human beings who were vulnerable, abused and in need.

Sadly, that was all to change in 1940. Put succinctly, with the success of the Nazi blitzkrieg in May and June 1940, and the evacuation from Dunkirk, the United Kingdom suddenly and unexpectedly found itself awaiting an invasion not by migrants seeking a better life, but by Nazi stormtroopers, and all the might of the German military machine. On 10 June, Italy’s Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, having sat on the fence for months, finally declared war on the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom government panicked – a word used frequently in later House of Commons debates to describe their actions. Mass arrests and internment were ordered for thousands of innocents – Germans, Austrians and Italians between the ages of 16 and 70, including many Jewish refugees, anti-Nazis and anti-Fascists – upon the basis that they might possibly be “Fifth Columnists” – persons who secretly supported the Nazi Reich or Fascist Italy, and intended to undermine this country’s security. They had committed no proven crime, many of the Germans and Austrians were Jewish refugees, and most of the Italians were small businessmen, restaurateurs and café owners who had lived in Britain for many years. However, to make sure that they could do no possible harm to our nation, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered that they be arrested and deported. Some Jewish refugees, with experience of concentration camps, committed suicide rather than be arrested again. The argument was that there was no time for fairness or justice or consideration of human rights, an invasion might come any day, and the Jewish, the political and the economic refugees had to be got rid of as soon as possible. They were held temporarily in often totally unfit accommodation. A number of requisitioned former cruise liners were ordered to carry thousands of these innocent refugees out into the North Atlantic [the hunting ground of German U-Boats] to deportation centres not then in Rwanda, but in Canada, and later Australia.

The liners were usually unescorted, and it was no doubt no surprise when the second deportation liner, the Arandora Star was sunk by a U-Boat on 2 July 1940. There were 1200 prisoners on board – Germans, Austrians and Italians. 146 Germans and Austrians died, including two Jewish refugees who appeared on Hitler’s Most Wanted List. 446 Italians died – two out of every three of the Italians who had been marched up the gang plank. Amongst those who were drowned were four men who were naturalised British citizens, and whose deportation was contrary to British law – they were Frank Hildesheim, Antonio Mancini, Gaetano Pacitto and Giovanni Parmigiani. In the urgency to get these “enemy aliens” out of the country, numerous mistakes were made.

The survivors were picked up by a Canadian vessel, and were taken to the port of Greenock, in Scotland, where they disembarked on 3 July 1940. Some were by necessity hospitalised, but 452 were fit enough to be returned to custody. However shocked and shaken they may have been by what had happened on the Arandora Star [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was not recognised in those days], and despite the loss of so many of their colleagues and friends when that ship sank, all of them were again deported only seven days later on a ship called the Dunera. This time they were headed for Australia, a voyage of 56 days. Again, two days out into the North Atlantic, their ship was torpedoed. Thankfully, on this occasion, the German torpedo did not explode. The quarters in which the prisoners were kept were simply appalling, and the prisoners were regularly abused by their guards during the voyage – they were both beaten and their possessions were stolen. When the truth about the muddle, panic and confusion of their deportation policy was eventually brought out into the open, the Government paid sums in compensation to hundreds of claimants whose human rights had been abused, but never officially admitted liability in court. Of course, this could not bring back those hundreds who had died.

Sadly, the author’s conclusion is that human rights will always be vulnerable to what a national leader or politician may think to be a more pressing problem. Not all national leaders pause to consider whether the proposed response to a current problem breach human rights, or is proportionate to the problem that has arisen. Too often perhaps it is simpler to brush basic human rights aside – and store them as a luxury for happier times?

Brian Lett KC, 4 King’s Bench Walk